The Origin of Fashion

From the earliest prehistoric garments to the the emergence of the first modern fashion designer; a brief and incomplete history.

When did Adam and Eve eat from the tree of knowledge and realize their own nakedness?

When did humankind first begin wearing clothes?

The earliest primeval garments were crafted from organic matter and have decomposed and disintegrated eons ago. We may never truly know. Yet, as anthropologists observe the use of language and tools among our not-too-distant cousins, the great apes, it is not implausible to think that the practice of decorating and adorning the body emerged well before we homo sapiens walked the Earth.

What we do know is that the oldest garment on record, the Tarkhan dress, unearthed in Egypt in 1913, is just over 5,000 years old. There is compelling evidence of thriving textile production going back as far as 30,000 years. The oldest known artifact to indicate the making and sewing of a garment of any kind is a 61,000-year-old bone needle found in South Africa’s Sibudu cave.

Some of the oldest costumes that have managed to survive are ceremonial raiments originally worn to indicate the wearer’s rank and role. This tells us that not only did the world’s earliest clothes help protect ancient bodies from the elements and sheath them in modesty, they also fulfilled a need and function as old as time immemorial, one that still heavily influences the clothes we wear today: the expression of status and distinction.

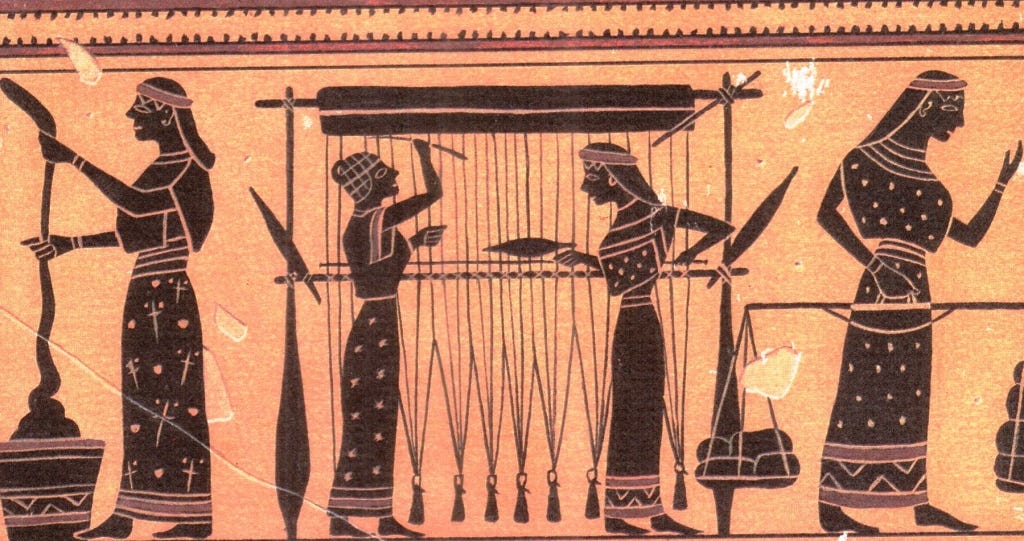

The production of clothing in the ancient world was labor-intensive and time-consuming. Once harvested and processed, tufts of staple fibers like wool and flax were hooked to a spindle and dropped. Gravity and the kinetic energy of its spin twisted the fibers into yarn. Long lengths of yarn were then staked and stretched across the ground on a y-axis (the warp), and then again on the intersecting x-axis (the weft). This was repeated over and over and that is how fabric was first woven. Eventually, vertically oriented, warp-weighted looms would replace this arduous process.

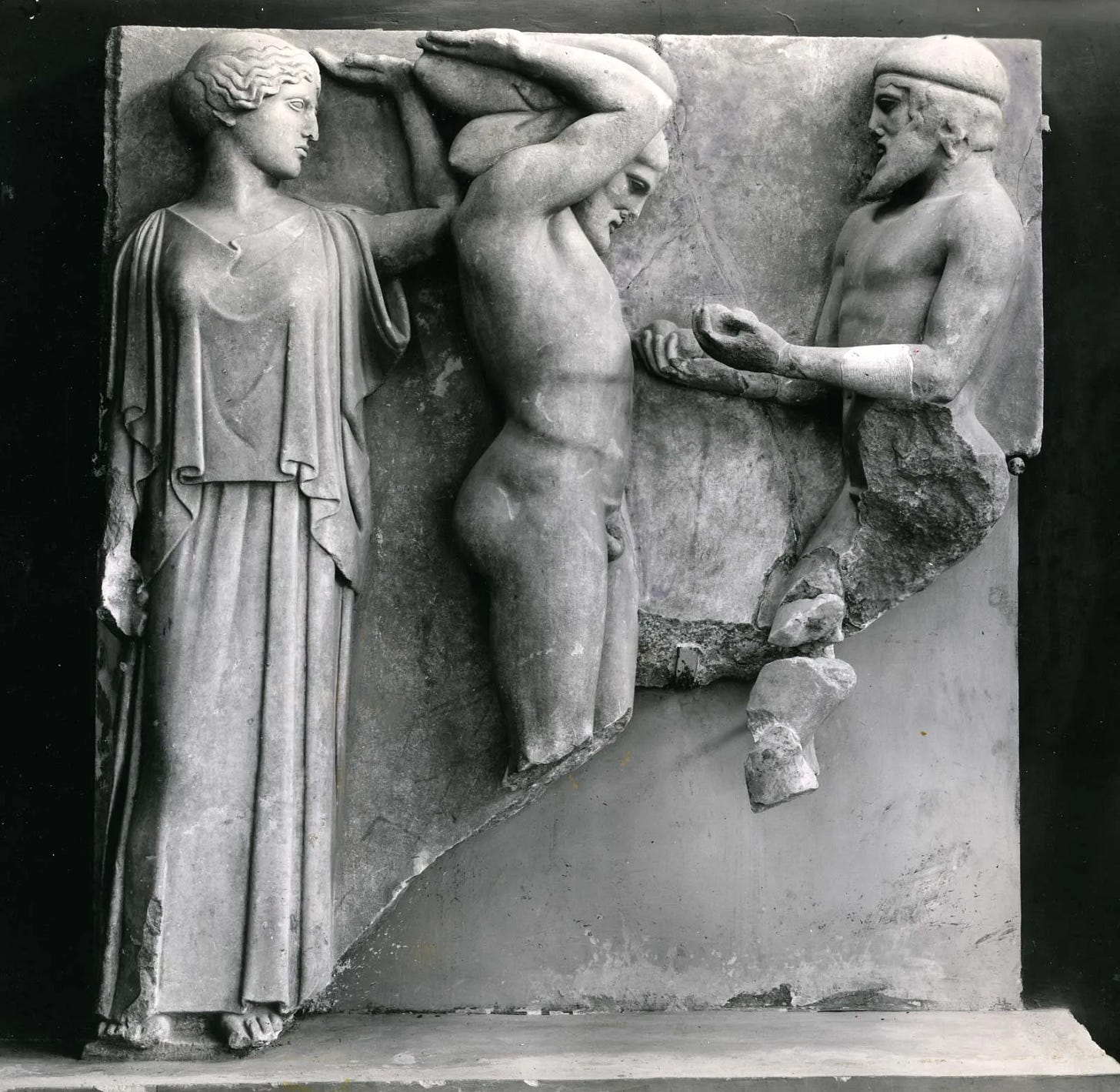

So precious and costly was the making of cloth in the ancient world that the Greeks deified the craft, using yarn as a metaphor for human life. In Greek mythology it was the three fates, Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos, who spun, measured, and cut the lifespan of every man and woman. So arcane and highly respected were the textile arts, that weaving was attributed to the goddess Athena who also presided over wisdom and warcraft.

Parallel to the origins of Western culture, the beginnings of Western costume begins in ancient Greece. The universal garment worn throughout the Greek city-states and their colonies was the chiton—a folded rectangular piece of cloth stitched or pinned at the shoulders. Popular imagination regards it as nothing more than a crudely draped bed sheet when in fact each piece of cloth was custom woven per the wearer’s specific height and width. Fabric was rarely cut and thus precious yarn was almost never wasted.

One common yet glaring misconception is that the ancient Greeks dressed entirely in white when in reality their fabrics were commonly dyed bright, vibrant hues and richly decorated with pattern and embellishment. Contrary to the neoclassical ideal, the ancient Greeks were, even by today’s immodest standards, gaudy and loud.

The Romans adopted Grecian dress by way of the Etruscans, and much like their adaptations of Greek religion, art, and architecture, they copied it meticulously while adding their own flair. One such item of flair was the toga—a crescent-shaped mantle worn exclusively by male Roman citizens. Ancient Greek garments were fundamentally based on the geometry of the square. Roman dress, and specifically the toga, added the sophistication of the curve, mirroring the architectural progression of the Roman arch from the Greek post and lintel. Another noteworthy Roman deviation from their Greek forbearers was the shift of textile production from the home to organized workshops and “factories.” The Romans may in fact be the inventors of what we would today call “ready-to-wear.”

Besides the toga, Roman citizens and non-citizens alike wore cloaks, capes, Romanized versions of the chiton, and tunics of varying lengths and styles. Roman dress disseminated across the conquered tribes of Europe but as the empire eventually weakened, it blended with indigenous barbarian garb. The amalgam of the two would become the basis of early medieval dress.

The Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE but its costume survives to this very day through the vestments worn by the Catholic church. They have persisted, virtually unchanged, for over 1,500 years.

The fall of Rome marked the beginning of the Dark Ages. Wealth, education, and literacy declined. Isolation, poverty, and political instability halted aesthetic pursuits. Medieval Europe was a grim and dangerous place. Relief from its oppressive dreariness came through religion and Christianity’s promise of salvation. It was widely believed by the medieval Christian world that Christ would return one millennium after his ascension. But then the 11th century came. And it went. And Christ was nowhere to be found. His failure to manifest and bring about the final judgment was interpreted as a second chance and inspired a new religious fervor, an enormous boom in churches (and the funding of new art and architecture), and an indomitable will to reclaim the Holy Land. And thus began the Crusades.

Expeditions to the Middle East introduced medieval Europe to spice, cotton muslin, silk damask, as well as Byzantine style and tastes. Significant economic growth spurred by trade and manufacturing brought about a new prosperity. Medieval costume grew increasingly more elaborate and diverse. Garments became more form-fitting and detailed—made possible through a larger, well-organized network of trade guilds. The late Middle Ages (around 1300) saw the emergence of the haute bourgeoisie—merchants, major landowners, and other entrepreneurs who commanded nearly as much wealth as the governing aristocracy.

And this is where it gets really interesting.

Before, it was easy enough to discern the ruling class from commoners for only they could afford the more costly clothes. The demarcation of power and authority was clear. But the new wealth of the haute bourgeoisie meant that they too could indulge in all the same finery and splendor. Power and authority is often a matter of perception. Seeing is believing. The lack of distinction between the aristocracy and the haute bourgeoisie threatened to undermine the natural order on which European feudal society was built. And this simply would not do.

Sumptuary laws were implemented to maintain the status quo but to little avail. Soon, the aristocracy picked up a rather curious habit. They began to alter and adjust their attire frequently, seemingly arbitrarily. Usually the changes were prescribed by the tastes and whims of whichever king, queen, lord, or lady held sway at the local court. Only those who had a place at court would know what the changes were and thus be able to follow along. Only those in-the-know would know the right thing to wear. And so a new strategy emerged to create distinction between the aristocracy and everybody else, to separate ‘us’ from ‘them.’ It is right here, at this very juncture near the end of the Middle Ages, just before the dawn of the Renaissance, that most historians agree is the origin of the bizarre cultural and social phenomenon, that tyrannical, culpable fiend: Fashion.

In German and French it is called mode, in Spanish and Italian it is moda. The Online Etymology Dictionary explains the genesis of the English word, Fashion, as such:

fashion (n.)

c. 1300, fasoun, "physical make-up or composition; form, shape; appearance," from Old French façon, fachon, fazon "face, appearance; construction, pattern, design; thing done; beauty; manner, characteristic feature" (12c.), from Latin factionem (nominative factio) "a making or doing, a preparing," also "group of people acting together," from facere "to make" (from PIE root *dhe- "to set, put").

The Fashion phenomenon is uniquely European and has only made its way to other parts of the world through colonialism and Western hegemony. Yes, certainly the costume and dress of India, China, or the Middle East have changed and evolved over time, but typically only over a very, very long period of time, centuries rather than decades. And usually only due to major political upheaval like a change in the ruling dynasty or occupation and subjugation by foreign invaders. Or both.

Anyways, back to Europe. Art, architecture, literature, and philosophy flourished during The Italian and Northern Renaissance and so did fashion and dress. The introduction of the spinning wheel from India, trade with the Ottoman Empire, and the development of more elaborate and luxurious fabrics like brocade and velvet contributed to a more stylized costume. Shape and silhouette grew more dynamic and robust, requiring more rigorous construction and understructures.

The invention of the printing press famously ignited the Protestant Reformation. It also sped up the dissemination of fashion through the publishing and distribution of fashion plates. The printing press is analogous to today’s Internet and it, along with frequent intermarrying of nobility between Europe’s various courts (and the obligatory gifting of a bridal trousseau), led to a new internationalism in fashionable dress. The epicenter of fashion influence was tied to military and economic dominance which ebbed and flowed through Europe’s major players like Italy, France, Germany and, especially in the 16th century, Spain.

The Baroque period that followed the Renaissance was a direct reaction to the simplicity and modesty advocated by Protestant dissenters. The Catholic response to denouncements of its unholy excess was an aggressive pursuit of an even more ornate aesthetic. Spanish work, cut-work, and other decorative embroideries, along with bobbin and chantilly lace, were in high demand. The silhouette ballooned to a massive, artificial scale, requiring even more elaborate support garments to maintain. All of this led up to what would be the apogee of European decadence: Rococo.

The reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715) saw the French Empire ascend to become Europe’s premier regional power which led to the centralization and consolidation of fashion dominance in Paris and Versailles. With his taste for all things sumptuous, Louis XIV indulged in lavish cuisine, architecture, interior decor, and dress. He was a great patron of both art and artisans. A brilliant, resplendent beauty emanated out from him, not only throughout the French Empire, but the whole of Europe itself. He was, without a doubt, “The Sun King.” Louis XIV’s demand for finery, as well the demand of those who wished to emulate him, sowed the seeds for a booming export economy that included wine, fragrance, fine jewelry, textiles and fashion. It is through him that not only fashion but luxury itself became inextricably linked with France—a legacy that has been inherited today, for better or for worse, by France’s richest man, LVMH CEO Bernard Arnault.

Rococo emerged in France in the 1730s. Its florid, curvilinear forms were a deliberate departure from Louis XIV’s more geometric look. As ornate and stylized as the Baroque period was, it was also somewhat serious and stoic. Rococo was playful (on the verge of silly), flagrant in its ostentation, and unapologetic if not prideful in its indulgence of grand, aristocratic idealism. Meanwhile in England, the early beginnings of the Industrial Revolution and a burgeoning consumer society were taking root. New weaving technology and the low cost of cotton (imported via the East India Trading Company) significantly increased the speed and lowered the cost of making clothes. Suddenly, Fashion was no longer limited to nobility and the wealthy elite. A broad, newly awakened audience catalyzed Fashion’s most significant mutation since its inception. By the end of the century, Fashion had become commercialized.

In the late 18th century, as the science-based, rational thought of the Enlightenment took hold, Rococo gave way to Neoclassicism. The shift was both political and aesthetic. The American Revolution saw a firm repudiation of England’s monarchy in favor of Greek-inspired democracy. In France, the empire went bankrupt due to a series of unsuccessful wars and drew the ire of the French people. In 1789, hungry and incensed by the aristocracy’s callous apathy, they revolted and stormed the Bastille. Marie Antoinette’s influential dressmaker, Rose Bertin, fled to London. In 1792 the French monarchy was formally abolished. Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were beheaded a year later.

In the years after the French Revolution, nearly every trace of the old regime was cleansed and vanquished. As a result, fashion underwent incredible, radical change. Breeches were discarded for long trousers (the costume of the working man). The voluminous, wide-hipped robe à la française was replaced by the high-waisted, columnar “Empire” silhouette which sought to mimic, if only superficially, the ancient Greek chiton. As the century got on, fashion would continue to evolve and move faster than ever before. The Romantic Period was a reaction against the Enlightenment and classical-inspired dress eventually fell out of favor. By the mid 19th century, immense, floor sweeping hoop skirts supported by crinoline cages had come into vogue. It was right around this time that Fashion would undergo its second and perhaps most profound mutation.

Charles Fredrick Worth was born in England in 1825 and apprenticed to textile merchants before relocating to Paris when he was twenty-years-old. He was a leading salesman for the Gagelin’s textile firm before convincing them to allow him to open and run a new dressmaking department. Worth managed to make a name for himself and in 1858 he partnered with Otto Bobergh to set up an establishment of his own. In 1860, one of his dresses caught the eye of the Empress Eugénie and by 1869 he was appointed the official court dressmaker. Worth was innovative not only in style but also in his approach to servicing clients. Historically, a client would dictate to the dressmaker what she wanted to wear. If she happened to be royalty or in a position of influence, that costume would then become Fashion. Worth flipped the script. Instead, he designed and and offered his own original creations which his clientele could then order for themselves. He was not just selling a dress, or even a beautifully and exquisitely made dress. He was selling his unique vision of fashion and peerless standard of excellence. Worth was the first to sign his clothes. He was no longer a mere dressmaker but in fact a sovereign creative entity whose taste, skill, and foresight gave him the authority to prescribe what elite European and American women should wear and when. Worth was the father of haute couture, but more than that, he was the first Fashion designer in the modern sense of the term.

And there you have it: a brief and incomplete accounting of the origin of Fashion. From the “Garden of Eden” to the emergence of the first professional Fashion designer, it is a story centuries in the making. Fashion would of course continue to change and evolve as the future was unlocked and the 20th century unfolded. It would be reshaped by the dawn of the modern age. The invention of the telephone and the automobile, the harrowing realities of two world wars, the intoxicating glamor of Hollywood, the fear of nuclear annihilation, the dizzying speed of life made possible by air travel, the promise of tomorrow of the Space Age, plastic, second-wave feminism, the avarice of industry and mass-marketing, the Information Age ushered in by the personal computer and the Internet, the homogenization of conglomeratization, and the proliferation of social media would all leave an indelible mark. In the first quarter of the 21st century, Fashion would be transformed into an entirely different beast.

But that’s a story for another time.

I enjoyed this very much and will have to read it again because there’s a lot to take in. Thank you for this well researched and informative post. I expected nothing less.

I knew I wouldn’t regret subscribing to your substack.